November. Vantage

Point.

I

took a while to present my stuff today because I was attempting to

reprise Szarkowski's final act. Vantage point on the face of it is

pretty straight forward, but he also provides some summary material

for the whole book including a definition of what a photographic

artist is all about. More about all that below and in the extras.

Simon

and I overlapped quite a bit with our approach to vantage point, I

wished to provide as many samples as possible, believing that we

learn visual things best from looking at lots of photographs. Simon

provided some carefully chosen images from his own work that gave a

more precise set of examples.

Greg

changed 'vantage point' to 'perspective' and quoted Szarkowski, “Much

has been said about the clarity of photography, but little about its

obscurity” as a springboard for his assertion that reality and

imagination rely on each other, - they interact. He showed us a set

of his own in-process imagery that combined origami with photography

- the constructed in the context of reality.

Homework,

I believe, asked for two images from the past year that for you best

exemplified what you got from the course. But I will provide an

update when I can get the exact wording. Or you could present images that relate to vantage point!

John

Szarkowski, in his book 'The photographer's Eye' has been placing

before us several aspects of the new art of photography that seem to

him to set it off from the older visual arts, “ ... an

investigation of what photographs look like, and why they look that

way.” Today we will be examining the last of these

characteristics - that of vantage point. We not only select our

subject matter but take our image from a specific angle. We select

our viewpoint and then capture, rather than create a synthesis as

would be more typical of a painting. Since, throughout the year we

have also been looking at portfolios of photographers who break with

this definition it is important to remember that Szarkowski is

working within the modernist tradition where photography first began.

Times change, the avant-garde moves the line forward into new

territory but the traditional approaches to photography still have

much to offer us all and may be revisited to find yet another

starting point when the present vogue begins to loose its sense of

purpose. For those of us who work with new ideas it is useful to

know, even if we reject them, where it all began and the qualities of

the foundation upon which we build new castles in the air.

Photography

has often presented, often relied upon, the unusual vantage point,

and in the beginning this strangeness disturbed viewers. To this day

through the multitudes of photographic images, our ideas about the

nature of reality are continually being challenged. We are still both

disturbed and excited. We see from another vantage point and receive

in the process another point of view.

Photographers from necessity

chose from the options available to them, and often this means

pictures from the other side of the proscenium showing the actor's

backs, pictures from the bird's view, or the worm's, or pictures in

which the subject is distorted by extreme foreshortening, or by none,

or by an unfamiliar pattern of light, or by a seemingly ambiguity of

action or gesture.

Photography

today is free to sample ideas from the long history of the visual

arts. Indeed, sometimes it seems that the camera, that potentially

expressive instrument, is simply used to document a scene created by

the artist, or to provide source material for photo-shopped

conceptual art. This, in Szarkowski's view, would seem to be a

failure to use the instrument well for what it does best and has

always done; directly recording the nature of reality - the thing

itself. However, the camera has always selected pieces of reality and

has always expressed the point of view of the photographer. The

present avant- garde of photography is simply an extension of, rather

than a departure from, photographic tradition.

Szarkowski

tells us that “An artist is a man who seeks new structures in which

to order and simplify his sense of the reality of life”. It may

seem a long stretch from Adam's and Weston's formal imagery to the

highly constructed and 'shopped' images or the simple 'selfies' of

the social media of the present day, but they all fit within his

definition. Times change and the camera has always held up the mirror

to whatever time it has found itself within.

The

influence of photography has been profound: we see reality, we

describe it to others, with thousands of photographs behind us

bending our perceptions. Not just other visual artists, but writers

and musicians make their images within this mind set. Even this

little essay could be seen as a series of snapshots: I expect my

readers to progressively 'see' my point of view.

Szarkowski

is working hard to make a special case for photography, but people

were making pictures long before photography arrived on the scene and

it is highly probable that the photographic image owes as much

to earlier forms of thought as present day photography does to the

photographic traditions of a hundred and fifty years ago.

But

Szarkowski is correct: the camera does have qualities that separate

it from other forms of visual art ( In fact through much of its

history photography was not considered capable of being art at all).

He makes a specialized case for a different way of seeing and making,

a particularly America one, even one that chooses certain

photographers he brands as characteristic and ignores others. Within

those narrow walls however, he has a sharply focused way of seeing

what photography is and can be. His ideas have been very influential.

He takes a series of slices and unfolds them for us. Finally we

arrive at the last slice: vantage point.

What

is our vantage point as we click the shutter and how well does it

express our point of view?

Extra

1

When

I began to seriously think about 'vantage point' I once again made

the mistake of thinking that this was simply Szarkowski stating the

obvious. Only when I started shooting in preparation for this lecture

did I discover how I unconsciously use vantage point. How my images

are often very finely honed to satisfy some important aspect of my

visual mind; one that does not usually begin with a concept developed

with words and then seeks an illustration for it, but is strictly

visual thinking seeking formal visual satisfactions. Finding the

precise vantage point and pausing with my finger on the shutter

release until everything in my viewfinder is correctly arranged,

until some special little relationship has perfectly set itself up

is, it turns out, the inner key to many of my most personally prized

photographs.

My

granddaughter accidentally strikes an interestingly dynamic pose atop

a driftwood stump in Ruckle Park, but I do not take the photograph

until I can line up the distant beacon in the triangle of her knee.

The 'negative space' is integrated into the composition. Value added!

The

two arbutus trunks bend to form a strong graphic shape. I visualize

how this would look in black and white, but before clicking I

organize the image by minute adjustments in my vantage point so as to

place the distant Beaver Point in precisely the right visual position

in the V of the tree. The composition falls into place. Satisfaction!

My

son in law and granddaughter are ahead of me, walking far out on

Rathtrevor Beach. The stripped down landscape at this low tide, all

beach and sky, places their figures in the context of immensity. But

before I click the shutter I dodge to the left so that their figures

are dead centre to those of two other couples in the distance. From a

potentially weak and floppy kind of distant image I have created

something of geometrical precision. Sea, beach and the line that

divides them, and a three dimensional triangle linking the figure

points. I have made a strong and ordered picture from this scene.

Yes!

The

light is soft, the scene indistinct; the camera has difficulty

auto-focusing and so I focus manually on the white seagull. Here is a

floating world wrapped in Turner-esque light, so I purposely leave

the gull in an off-centre, intermediate place in the composition to

emphasis the mood and click away. Later, I sharpen the waves in the

foreground. A high key composition, vague, soft, dreamy... a

reflection of the moment itself!

In

my own mind these picky little visual alignments make art out of

'reality'; make intentional imagery of the kind Szarkowski describes:

“An artist is a man who seeks new structures in which to order and

simplify his sense of the reality of life.”

(

We notice “An artist is a man....” and mentally translate more

inclusively and correctly as “Artists are those who...”) :)

This

quality of order and structure in art ( and we are studying ART

photography remember) works on a variety of levels. At the craft

level we may simply apply a conventional rule of composition to

whatever image we make - the rule of thirds for example –

irrespective of what we may wish to communicate. Perhaps we have

nothing else in mind than superimposing a familiar structure on our

piece of reality that will supply our and our viewer's mind with a

satisfying sense of order. Art, in comparison, seems to be vague and

intuitive, shy of formulaic solutions and yet, even as it seeks to

poke us in the eye and wake us up, it still needs to find the right

structure for the idea it wishes to communicate. That is why it is

valued so highly of course, each work is, ideally, an individually

perfect solution to communicating a specific idea.

I

wrote a little piece on Dragongate to go along with my beach photos:

Extra

2

The

other ( rainy) day I walked with a friend down at Indian Point and

took a series of photographs which capitalized on her yellow

rain-gear. I used a variety of vantage points and was also careful

not to include her face so there would be no problems with copyright

permissions etc. Also, no facial identity made her more universal,

less specifically an individual and easier for us to both identify

with and yet see the figure as part of the overall composition.

Here

the figure is more dominant but turns away to lead our eyes too into

the scene. From this vantage point we look over her shoulder and are

invited to see it through her eyes. The figure has a function in the

composition.

The

figure is small and isolated in a lonely grey seascape. My distant

vantage point and wider angle lens emphasizes this and expresses my

point of view about our human place within the reality of the world.

The distant ferry is an important visual element here because it

leads the eye ( and thought) from figure to ferry thus completing the

third leg of the triangle composition begun by coastline and branch.

Turns

out that vantage point is the angle from which one takes the photo

and also the degree of zoom or how close we are. They work together.

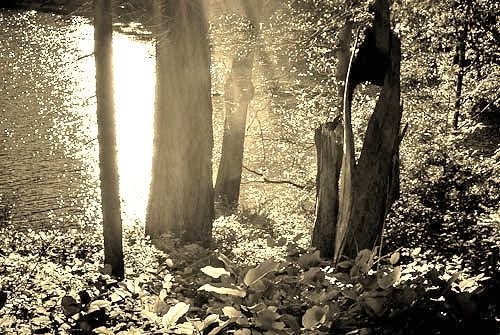

Viewed

through a screen of branches and the last back-lighted tattered

leaves of Fall, the seascape is much more expressive than if it was

photographed without this compositional framing devise. Vantage point

is a powerful and expressive photographic technique.

Extra

4: Visualization: from vantage point to point of view.

In

my photo presentation I showed a number of images, my own and those

by more experienced photographers, and was struck by how the ability

to pre-visualize was present in the finished images. In particular,

the powerful photo of John and Yoko, by Annie Leibovitz, taken

earlier on the day he was shot to death, suggests a degree of

intuition of all concerned that is weirdly prescient.

My

own sketch for a book illustration project, first in pencil and then

photographed and placed in Lightroom' for the tonal work, requires

the ability to visualize and build a scene from scratch, and yet

photographic seeing may have been influential in choosing the angle

of view, the perspective and the light. How much more 'real' the

cabin seems because it in the guise of a common photographic vantage

point using a wide angle lens and yet how different it is from a

photograph in execution.

The

images from David Blackwood of his childhood memories of Wesleyville

on the far east coast of Newfoundland were chosen because the

photograph's chief value over time has been as a documentation of the

present for its value in the future. Blackwood uses his memory rather

than a camera to create images of a vanished way of life. The

question could be, as Szarkowski mentions, to what degree has the

photographic tradition influenced the engravings presented here? How

much have old b&w images influenced the artist’s way of

presenting his personal perspective?

When

making a photograph I know that I pre-visualize the finished image

even as I see the photograph I wish to take, and adjust my shoot to

suit: this is where vantage point blends with view point and then

becomes a personal point of view or 'take' on the world. I know that

this process is not unique to me but is a skill common to most

photographers. Can it be learned or is it built into us individually

from the beginning?

Extra

4 Rational versus intuitive.

What

is art? Questioned, Picasso answers: “ Even if I knew I wouldn't

say!”

The

artist paints, dances or composes his revelations.... For artistic

intuition emanates from the cosmos and embraces the whole world.

Colour

creates Light. Studies with Hans Hoffman Tina Dickey

Flat

grey sky, a long strip of black islands and something dark and ill

defined on the sea's edge behind the crest of a breaking wave. For me

this has a power to set my teeth on edge. It is a disturbing image

out of all proportion to “dark day, ferry wave”. There are some

images that Jung would describe as coming from our remote human past

that bring up strong reactions. Perhaps a great white shark, an Orca,

or a crocodile surges out to snag us off the shore and our first

instinctual reaction is out of proportion to the present reality. We

feel it, even though we may not be able to tell the reason why

through standard compositional analysis or through ideas about what

constitutes a 'good photograph'.

One

of the problems involved in teaching the arts is that on the one hand

an instructor wishes to present information that people can get their

minds around, and on the other to shrug and say that really there are

no rules and the whole process is intuitive and mysterious.

Szarkowski performs a series of cross sectional scans of photography

and step by step presents us with some conclusions that with effort

and practice we can incorporate into our own way of seeing. Well and

good, and thank you for this John. How is it then that often as not

the images that touch us do not seem to follow rules at all? Or that

we seem to take our photos intuitively and only later analyze them in

terms of composition. In photography the `thing` we capture is all

important, as though we the photographers are at the mercy of

powerful chance, as though our subject has us by the neck and draws

us like an arrow in a bow to the final shutter release. Weird stuff,

and irrational, but in the end it is not wholly fancy equipment or

practical training that produces the most telling images.

Extra 5

'What, how and why' and

Szarkowski's emphasis on 'reality - the thing itself'.

An

artist is a man who seeks new structures in which to order and

simplify his sense of the reality of life. For the artist

photographer, much of his sense of reality ( where his picture

starts) and much of his sense of structure or craft ( where his

picture is completed) are anonymous gifts from photography itself.

The photographer's Eye. John

Szarkowski

When

we ask “what is art or who is an artist?” we can get confused by

the variety of definitions. Szarkowski was the curator at the Museum

of Modern Art so we have to take his definition seriously, even as we

recognize that here he is cutting it to fit the new form of art -

photography. In an era dominated by abstraction he makes a case for a

unique photographic art form oriented towards reality. He presents

those qualities that mark photography as different from abstract and

non objective painting.

One

way of understanding why he puts so much emphasis on reality

is to think of our human drive to make images, which has been an

important part of our behaviour as far back as we can imagine, as

central. In the past and in the present we as individuals and as

societies see the world around us and we ask the question “What

is this thing we experience as reality?” We explore this by making

images, by music, by dance and through language. So, there is the

world out there but we are part of it too and our human way of

dealing with it is also part of reality.

If

we ask what and why this reality is, we touch on

religion and in the visual arts of Christian western societies for

the past two thousand years this tie has been very strong. If we ask

what and how this is, we touch upon another important

way of approaching reality – through the magnifying lens of

science.

Szarkowski's

important way of defining photography, by concentrating on what

and leaving the other questions to be imagined by the viewer is

well suited to photography and its instrument the camera, which

records in detail – the thing itself. His ideal photographers are

ones like Weston and Adams who, theoretically at least, favour clear,

sharp images of nature in all its forms: reality. And that at least

is a narrow, clear cut way of defining photographs and relating them

to the larger world of the visual arts.

Now,

he is aware that an individual photographer does not work in

isolation, that he too is immersed within a society and is influenced

by other photographs and photographers. We all start by confronting

reality ( the what) but how we see it and how we take its

picture is conditioned by every other image we see around us. (Just

go to a photo site like photo.net and see how closely all images

conform to one another) . Hence his insistence on the Modernist

agenda to seek “ new structures”. He tells us that photography

works well when it is keyed to reality and that each of us is

responsible for finding our own original ways of recording its image:

that's the art.

A

lot of effort in society goes into arguments about various

definitions of art and this is part of a natural process of finding

'new structures' and is a central tenet of Modernist philosophy that

has been a standard in photography since it was invented. We are

inheritors of this 'progressive' way of thinking and it pervades all

aspects of western societies. In science we pursue 'how' and ask it

to provide newer and more refined answers. Religions are expected to

explain the 'why' of our lives in regularly updated and more modern

ways.

Art

photography, Szarkowski seem to be insisting, should concentrate on

keeping a clear vision of reality ( the what), and

photographers need to focus on Seeing first and foremost and using

their cameras to clarify, record and communicate 'the thing itself'

to society as a whole. This would place the photographer within the

role that western artists have occupied since the first cave

paintings in Europe thousands of years ago: makers of 'structured'

images that reflect the reality of the world*.

*The

first point to grasp is the immense fecundity of humans in

producing objects of art. I argue here that art predated not only

writing but probably structured speech too, that it was closely

associated with the ordering instinct which makes society possible,

and that it has therefore always been essential to human happiness.

ART. A new

history. Paul Johnson

Extra

6: Peering through the doors on perception

The

most important duty of all is to look at art long and often, and

above all to look at it with our own eyes. Facts are external and

need to be learned. But the love of art is a subjective phenomenon,

which comes to us through our subjective eye, and no expert should be

allowed to mediate. In the end, our own eyes are the key to making

art our guide and solace, our delight and comfort, our clarifier and

mentor. We should use our own eyes, train them, and trust them.

from

Art: A New History. Paul Johnson

We

are at the end of a year's study of Photographic art: with Bill we

have examined the American modernist writing about photography of

Szarkowski and learned to both value and question his point of view;

we have learned the practical aspects involved in making art

photographs through the eyes and practice of Simon, and finally with

Greg we have had our treasured beliefs challenged through works of

post- modernist photographers. We have peered through many and varied

doors on perception and are now set free to come to our own

conclusions and to develop our own perspectives and ideas about our

best personal practice.

The

above quote talks about viewing art but of course it applies even

more urgently to the makes of art, to us with our cameras. May

we look so hard that we begin to See and may we see so well that our

photographs take on a life of their own.

.jpg)

.jpg)

%2B(800x496).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)